After a year of spending a £10,000 travel prize, Roger Williams looks back on the countries he visited - with the help of a 5th century BC chronicler

LAST YEAR I won the £10,000 Dorling Kindersley-Rough Guides Dreamtrip prize. I could use the money however I wanted, go where and how I pleased. Where would you go? What would you chose? It was a good question. Long-haul travel has never interested me much while there is so much to see nearer home, and in the end, I simply plumped for cities and countries I had often thought about. What did they really look like, who lived there, what did they eat, how did they speak and dress, and how did it feel just to walk down their streets.

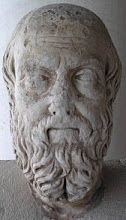

The destinations, from Russia to Egypt, were all in a relatively small area of the globe, an area, I discovered afterwards, that was reported on by Herodotus in The Histories. The 5th-century BC Greek chronicler set out to meet people of different races and see for himself the known world, and in so doing he hoped to discover why nations so frequently went to war, and in particular, the origins of the apparently endless feud between East (Persia) and West (Greece).

Greece was the country I visited when I first went abroad, and it was here, during the days of a stupid and brutal dictatorship, that I learned how much one country could dislike and misunderstand another, and how much history could be blamed for troubles that exist today. The Ottoman Turks, many Greeks believed, were responsible for much of the country’s ills; centuries of occupation had resulted in the stunting of economic, social and political development, while prevailing problems were exacerbated by Cyprus where tensions were being expoloited by the West, and politicians were beginning to say that the two nations could never get on.

The empire that preceded the Ottomans’ was Byzantium, a largely Greek-speaking world that held together the vestiges of the Roman Empire in the East, from Romania and Bulgaria through the Middle East to Egypt. After the fall of Rome in AD410, Constantinople (Istanbul), capital of Byzantium, declared itself the Second Rome. And after Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the title moved northwards up the Dneiper, following the early missionaries, to Moscow, which took on the mantle of The Third Rome. The Romanov tsars used the two-headed eagle of Byzantium for their own flag, and the eagle, on a yellow background, was flying outside the churches in Salonica at Easter. It remains the symbol of the Greek Orthodox Church, whose patriarch still resides in Istanbul.

Land of the falling feathers

Moscow and St Petersburg were the first places I visited with my prize money. In terms of conflict between East and West in the modern world, Russia cannot be excluded. Herodotus never visited Russia, though he was told of lands that were showered with “feathers”, a rumour he correctly interpreted as having heavy winter snow.

Moscow would like to think of itself as a world city but it is not a cosmopolitan city. It possesses only an internal internationalism, which can be detected among the few Asian-looking people on the metro. Throughout the day Muscovites travel on these efficient trains in complete silence, not reading, not talking, not misbehaving. Russians travel little themselves and do not, as a consequence, like foreigners, who are regularly blamed for anti-Russian slights and assorted crimes. Muscovites do not even like the people from outside who come to the city to find work, for which permits are required. It cannot always have been like this. A large, 19th-century painting of Moscow’s Chinatown, now in the Russia Museum in St Petersburg, shows the city as a much more exciting, cosmopolitan place. And as for the beautiful churches and cathedrals that have survived inside the Kremlin, their frescoes and icons in tact, these show the heights to which the Russian spirit is capable of soaring.

While the rest of the world might see the land of Anna Kerenina and Tchaikovsky as a cultural powerhouse, Russia doesn’t see itself that way. It is only three decades since it was a superpower, two decades since it was all but bankrupt. Nobody who was once rich but is now poor can help feeling bitter. The rich like to believe they are rich because they deserve it, while the poor believe that it is the fault of the rich that they are poor. Russia is not alone in finding its former glory hard to forget. People everywhere – Catalans, Lithuanians, Serbs, Bulgarians, Poles – hark back to times when their country was powerful, and dominated a larger slice of the world. Yet they are unable to relate this to their own despair and frustration when it is their turn to be doninated by another nation. I am a benign ruler, you are a tyrant.

Western horizons

Why have nations always looked to the west? Wave after wave of tribes came out of the east – Mongols, Huns, Slavs, Turks – all chasing the setting sun. Were they trying to find out where it went? Peter the Great took the West as his model when he built St Petersburg from the swamp up. The new capital could be anywhere in Europe, unlike Moscow, whose Eastern onion domes made him ashamed. His court spoke French: magazin for shop, etage for storey are among many words now embedded in the Russian language. French pervaded upper-class society chatter in the last days of the Ottomans, too, and I was once in a house in Greece where the entire family spoke French among themselves. Even then, in the late 20th century, Greek was thought an inferior language.

Tsar Peter was creating the Hermitage when Louis XIV was reaching his high noon at Versailles. Little more than a century later Baron Haussmann was puling down Paris, and blame can be laid at his door for ruining many places that sought to emulate Paris of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Old cities such as Cairo, creaking with unique vernacular architecture, were rebuilt to make way for buildings of the same European design. Just as the symmetry of Rennaissance architecture had smothered the natural, instinctive hand of man, so neoclacisism came down like so many tons of well ordered bricks.

In Turkey in the 1920s and 30s, reforming Atatürk looked to the West’s functional, modernist style. All things Ottoman, many of which had a fin-de-siècle grandeur, were officially despised. Atatürk had saved the Turkish nation from being devoured by the great powers after World War I, when it had backed the wrong side, and by Greece, who had hoped to extend its territories across Anatolia (Greek for ‘rising sun’, or east) to the Pontic lands of the Black Sea. His Westernising zeal included the introduction, within three months, of a new written Turkish language using Roman rather than Arabic script, which cut off the nation from much of its history. It also included the banning of the fez. But Turkey, like Egypt, is still a pleasure to travel in simply because people do still wear national dress.

Ruling gods

Politically, socially, leaders may have looked to the West, but religion burns along a different path. Herodotus visited Egypt to find out if the Egyptian gods were older than the Greek gods. Monotheists were not interested in such things. The Temple of Philae in Aswan was relocated to an island when the dam was built, with Russian help, in the 1980s (Russians travelled to Egypt in great numbers in Soviet times, but with the collapse of communism they abruptly stopped.) Now beautifully sited, the temple’s huge reliefs of the gods were shockingly damaged with the blows of angry hammers, delivered by early Christians. The same patterns of destruction mark the frescoes of the Orthodox Christian churches in Salonica, the work of Islamicists many centuries later.

Nobody in Egypt worships the ancient gods now, nor do they in Greece, where such practice has recently been legalised. But Christianity has returned whole-heartedly to the Third Rome. The newly-built Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow is an astonishing glitter-ball of gold and marble, and it is hard not to look at it without thinking of the kings in the time of Herodotus appeasing gods with great treasures.

In southern Turkey signs over the icon emporiums in Myra are all in Russian. This is the birthplace of St Nicholas, supposedly Santa Claus, and a Father Christmas statue now stands incongruously in the warm sunlight of the central square, surrounded by these large shops selling silver icons made in Italy and Greece. The shop assistants have all learned to speak Russian.

Racial mix

Religion is one thing that helps to cohere a nation, to bring social control. Another is race. Egyptians have particularly distinctive physical characteristics – arching noses, high foreheads, smooth skins - that made them seem the most racially pure of all the countries I visited. In Aswan there were also Nubians, a very dark and beautiful people. Yet no Egyptian I spoke to knew any Nubian words, not even hello.

Russians believe themselves to be the unsullied Rus, despite Viking and Mongol Tatar invasions. In fact some historians believe that Russia’s bullying culture comes from the Mongols, but that is not something you should mention to a Russian.

In Turkey, even after being installed in power for several hundred years, the Turks saw themselves as disadvantaged by Armenians, Greeks and Jews, who shared the modern state, and Ataturk passed laws that would favour Turks in business. Still today you can hear Turkish people blaming the non-Turks for dominating the business world, leaving the poor honest Turk to agricultural toil. Yet like Russians, Turks can be insular. Istanbulites are not keen on any influx of countrymen to their city. This is a large country, and the east, bordering Iraq and Armenia, is a backward land to look down upon.

The Ottoman empire had been administered by “millets”, a system of local government in which each community had a selected Muslim, Christian and Jewish leader to look after their own kind in local affairs. This is well described in Ivo Andric’s novel The Bridge over the Drina, which gives the history of the Balkans through the story of events that have taken place around this 16th-century stone bridge in the town of Visegrad in Bosnia Herzogovinia. Nearly two decade after the death of this Nobel Prize winning author, in the course of the Balkans conflict, hundreds of Muslims were hurled into the river from this same bridge in a programme of ethnic cleansing, their bodies once even blocking up the hydro-electric dam downstream. Religion was invoked to define the battle lines in the break-up of Yugoslavia, which showed the astonishing depth to which human intolerance can plunge, and that it can do so as easily today as it could in Herodotus’s time.

Greece fell short of actual hostilities with the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia on its northern border. In Salonica, once the second city of the Ottoman empire, fury about the naming of the country of Macedonia remains. How can people who live in Yugoslavia call themselves Macedonians? Macedonians were Greek; their great kings, Philip II, who united the Greek states, and his son, Alexander the Great, who created the largest empire the world had ever seen, came from here in modern Greek Macedonia. People in Yugoslavia don’t even speak Greek. They are Slavs. And it is true that the Greek Orthodox church held together the Greek peoples for centuries. In fact, they were without a nation for longer than the Jews.

But what of the other people who don’t have, and never wanted a nation, such as the Vlachs? And what became of the Spartans and Scythians, the Phoenicians and Phrygians, the Zoroastrians, the Tatars, the Huns?

The truth is that there is no such thing as a nation until men decide that there is one. And then, having won or lost the wars that shaped them, they will start writing their own histories. It is up to the traveller to discover the truth.